Stringer/Anadolu Agency via Getty Images

- On February 1, Myanmar's military seized control of the country, detaining elected leaders and installing a new regime.

- In the months since, security forces have killed hundreds as protesters have taken to the streets.

- Three Burmese expats told Insider they've felt heartbroken and helpless watching the violence from afar.

- Visit Insider's homepage for more stories.

In the early morning of February 1, Saw Kapi was awakened by a phone call from a close friend.

Military trucks had come to the house of a leader of Myanmar's National League for Democracy party, the ruling party at the time, and soldiers had stormed his compound, arresting the politician right before his wife, Kapi's friend told him over the phone.

As director of the Salween Institute for Public Policy, a think-tank based in Myanmar's largest city, Yangon, Kapi had met with the now-detained politician just one week before.

Nervous, but not yet panicked, Kapi said he began making calls to other politicians and public figures, trying and failing to make contact with anyone in the government. Finally, he reached a junior-level staffer who delivered distressing news: Nobody had been able to reach any member of Parliament since the previous day.

"So, basically the communication was cut off completely early morning of February 1, and that's how we knew there was a military coup," Kapi said.

That first phone call proved to be a harbinger of the tragedy to come in the weeks and months following the military's power grab.

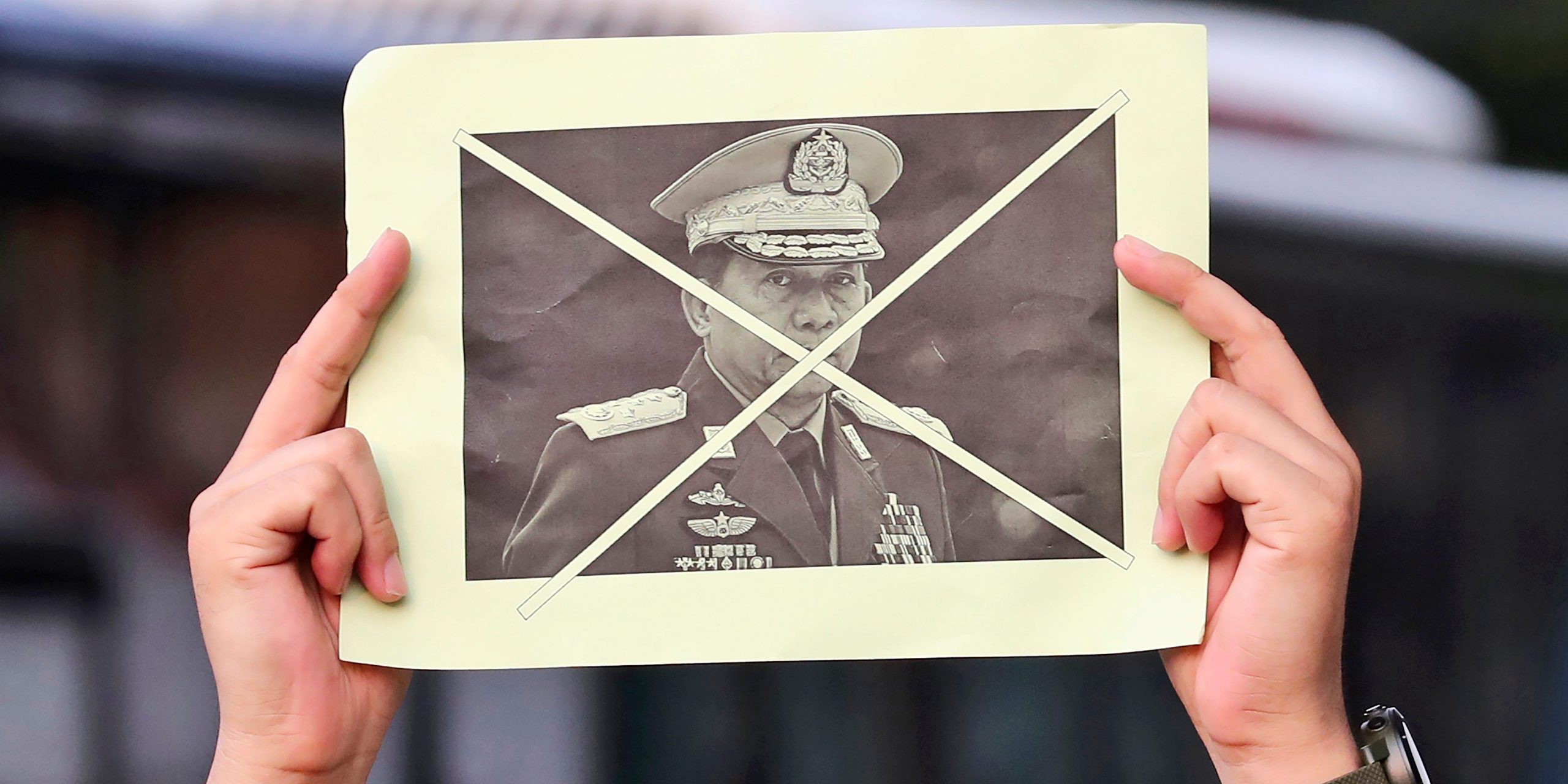

On February 1, the day the newly elected parliament was scheduled to convene, Myanmar's commander-in-chief of Defense Services, Min Aung Hlaing, announced the military would be taking control of the country for at least a year, citing unfounded claims of voter fraud in a November election won handily by the National League for Democracy. Prior to the announcement, Myanmar's military, the Tatmadaw, had detained State Counselor Aung San Suu Kyi, President Win Myint, and several other political leaders.

The 64-year-old Min Aung Hlaing, a long-time military general, wielded significant political influence even before the coup. But his time in power was running out; he was due to step down from his position in July, after reaching the retirement age of 65. By seizing power on February 1, he assumed all state power as commander-in-chief and guaranteed himself at least one more year in control.

In the months since the coup, the military has launched an all-out campaign against its own citizens, who took to the streets in protest almost immediately. Three months after the overthrow, more than 800 Burmese people have been killed, including upwards of 40 children, while more than 5,000 have been arrested and more than half remain detained, according to Myanmar's Assistance Association for Political Prisoners.

But even in the early days of the chaos, the scene was one all too familiar to Kapi, who had already once fled a Burmese dictatorship during the harsh crackdown that followed the country's 1988 democracy uprising. He spent five years at the Myanmar-Thailand border fighting in a rebel army against the coup makers before immigrating to the US in 1994.

Now, back in his home country more than 20 years later, no longer a rebel, but a prominent policy leader, Kapi faced a difficult choice. Not only had he begun partaking in mass protests, but rumors suggested targeted arrests were on the horizon, and his visa to stay in Myanmar was set to expire in March.

"So what I had to decide was... whether I leave with a [US] Embassy-arranged relief flight...or I will never ever be able to leave the country again," Kapi said.

He spoke to his wife and they analyzed the situation, weighing the growing risks as soldiers began conducting nighttime arrests throughout the country. Then, on February 26, the couple left Myanmar for the US, unsure when - or if - they'd be able to return.

Stringer/Getty images

Three Burmese expats told Insider it's been devastating to watch the destruction of their home from afar

Pwint Htun, a Myanmar fellow at Harvard University, grew up in rural Myanmar before her family was forced to leave the country after the 1988 uprising. Htun and her family found themselves in Thailand, where a serendipitous meeting with her American expat neighbors, led to a study sponsorship in the US when Htun was 18.

By the time Htun returned to Myanmar to visit in 2012, she had a degree in electrical engineering, a master's from Northwestern, and experience at Harvard's business school. She told Insider she wanted to help the people she had grown up with. For most of the last decade, Htun, as an executive in the telecommunications industry, focused her work on bringing mobile financial services to Myanmar's poor.

"I've been able to give back in an extremely impactful way," Htun said. When she first returned in 2012, Myanmar was the third-least connected country in the world, she said. But by 2021, "94% had access to 3G or 4G coverage."

Another Burmese expat and one of Htun's close friends also found himself in the US after a childhood in Myanmar.

San Wai Oo, a senior director of engineering at Slack, left Burma for Berkeley in 1999, seeking the higher education opportunities that were no longer available in his home country following the military crackdown.

At 22, Oo spoke no English. He started as a dishwasher in a college cafeteria before working his way through a litany of positions at some of Silicon Valley's top companies. But like both Htun and Kapi, he kept Myanmar and her people close to his heart.

"The journey that I have gone through and Myanmar, they have shaped me into who I am," Oo told Insider.

Among the three expats, an overwhelming emotion has proved prevalent since February's coup: survivor's guilt. Guilt for escaping a dictatorship once before and heartache for those left behind.

"You have survivor's guilt if you had to leave ... your friends in the country while they continue to engage in this protest against the military regime," Kapi said. "They're facing a very bleak future and difficult situation."

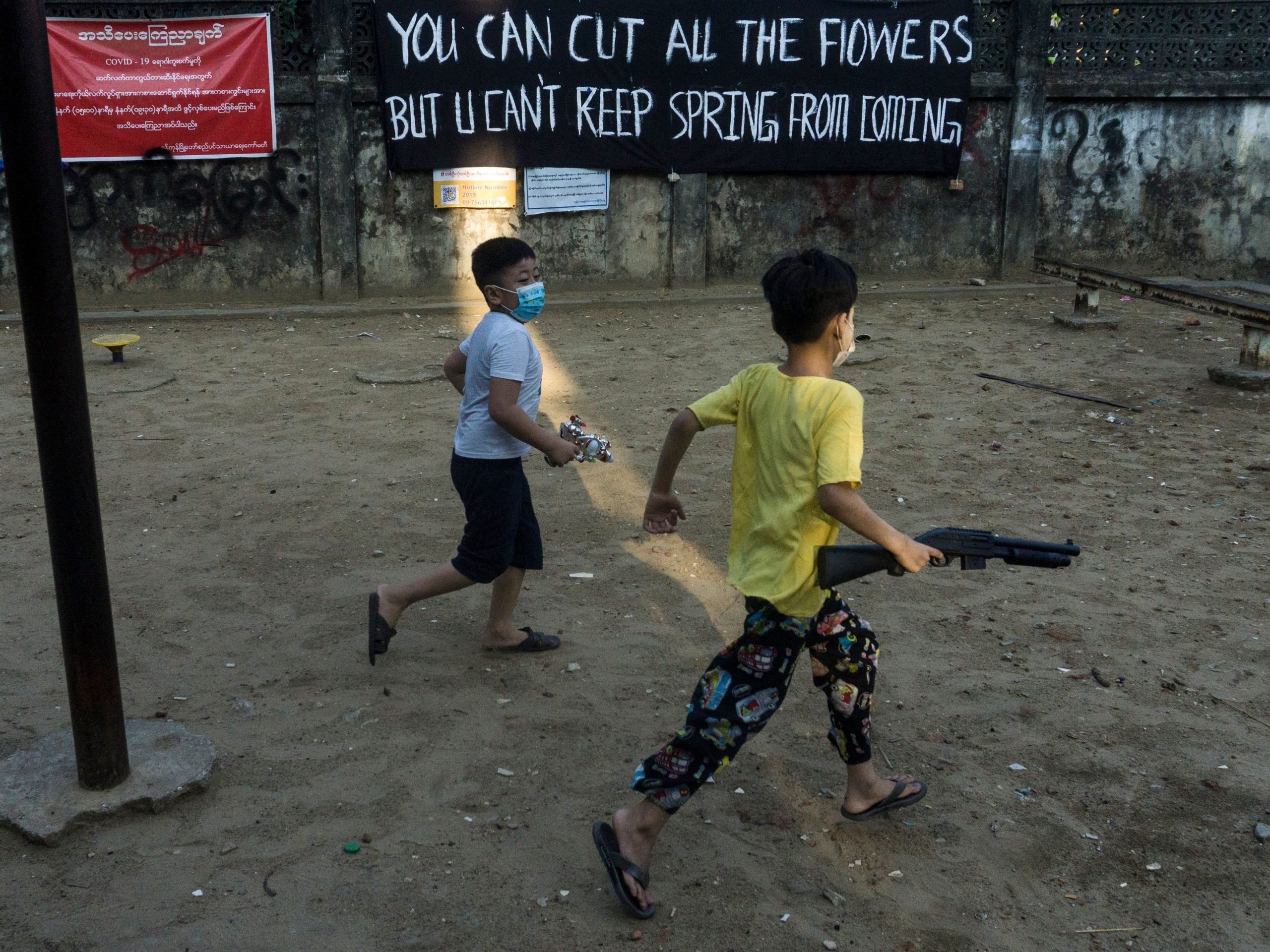

Photo by STR / AFP) (Photo by STR/AFP via Getty Images

Memories from a violent chapter of Myanmar's history haunt today's crisis

Until 2011, Myanmar (formerly Burma) had been ruled by one of the longest-held military dictatorships in the world. That regime began to loosen its control over the country in 2010, returning some political and civil freedoms back to the Burmese people. But even as the country propelled toward democracy in the years following, the scars of Myanmar's past never fully healed.

A military takeover in 1962 crippled the resource-rich country economically and democratically for decades to come, and according to Htun, today's commander-in-chief, Min Aung Hlaing, appears to be taking inspiration from his dictatorial predecessors.

"These dictators, even though they are in the 21st century, their mindset is very much looking at 1962," Htun said.

After nearly three decades of totalitarian rule, a student uprising in 1988 led to a nationwide strike known as "8/8/88." The democracy movement was imbued with a widespread feeling of hope among the young protesters when they secured the resignation of Ne Win, the military commander at the time, who promised a multi-party political system on his way out.

But only months later, the military retook power, imposed martial law and draconian laws, and continued to violently break up any remaining protests. Though an official death count has never been determined, Human Rights Watch estimates thousands were killed.

AP Photo/File

Kapi, Htun, and Oo all witnessed it first hand.

"My mother being a physician was seeing all these soldiers killing thousands of unarmed protesters and as a doctor, she couldn't just watch the people being killed," Htun said.

Her mother started organizing with medical students to provide treatment to injured protesters who were unable to seek treatment at a hospital for fear of being arrested. But as the military ramped up arrests, Htun and her family were eventually forced to leave the country.

"History is repeating itself all over again at the moment, and I think that has been really heartbreaking," she said.

Oo, meanwhile, left Myanmar for good in 1999 because of the devastation wrought by the crackdown. The majority of protests during that time were led by the younger generation, particularly students, Oo said. As a result, the government shut down many universities.

Oo said he was one of the "lucky individuals" who was able to get out and continue his studies in the US.

But for Kapi, who observed the bloodshed up close as a rebel fighter, the differences between 1988's crackdown and today's are as disheartening as their similarities.

"In 1988, the people protested against the government first. The protests were going on for a few months, then the military took over power of the country," Kapi said. "But in 2021, the country was in a perfectly fine position. Nobody was doing anything...but the military took over power."

The other notable contrast? The invention of cell phones and social media that, today, serve as recording devices and publishing platforms. In the 80s, those in small towns were often unaware of occurrences in bigger cities, Kapi said.

Photo by Theint Mon Soe/SOPA Images/LightRocket via Getty Images

"We are in a completely different era," he said. "People know who is protesting and where. There are images, clips, and video all over social media."

But the military's ongoing crackdown on internet access since February has only highlighted its necessity to the cause.

Internet outages and security concerns have made it difficult for the expats to keep in contact with friends and family still in Myanmar

Oo told Insider he has childhood friends still in the country, among them a college professor and a doctor. Oo was able to keep in touch with them sporadically following the coup, but both have since been forced into hiding after becoming military targets.

"I haven't been in contact with them for quite some time," Oo said. "I don't know where they are."

Kapi, as a resident of Myanmar for the last seven years, said he and his wife have several close friends still in the country, some of whom were detained during the initial coup on February 1. Much of his staff at the Salween Institute remains in the region as well, though he worked to relocate them to the Thai border following his departure.

Htun, meanwhile, said she's been inundated with horror stories of the military's "lawlessness" and corruption from her contacts in the country. In one township, she said soldiers raided a family's condolences fund after a death.

Photo by STR/AFP via Getty Images

Another friend owns a small convenience shop. One day, police officers started taking items from the shop, she said. When the cashier asked for payment, the soldiers beat him, she told Insider.

"When you are being robbed by soldiers and the police, who are you supposed to call?" Htun said. "It's that feeling of betrayal when the people who are supposed to protect you, who have sworn to protect you, are abusing you."

For the expats, the coup has prompted them to give back

The military's crackdown on personal property rights and the ongoing internet outages, have meant much of the progress Htun made in bringing mobile services to the country's poor has been wiped away, she said.

"The hopes that I had for the rural people to be able to lift themselves out of poverty, that dream got squashed away, really," Htun said.

For Oo, his heartache and despair prompted him to find productive ways to contribute to the movement. Through his professional network, Oo began sharing his story and raising funds for those still in Myanmar.

Oo told Insider he was inspired to donate half his salary to the cause after witnessing the generosity of those on the ground who donate to the movement, despite having very little.

"I see street vendors giving away free food to protesters and people who participate in the civil disobedience movement. I know the struggle they have, how poor they are, and yet, they donate," he said. "And I think 'oh my goodness, why am I even hesitating to do that?'"

He's also trying to educate his 9-year-old son about what's happening, but said he "can't tell him the whole story." The military's reckless murder of children since February has made their conversations even harder.

"All this sadness and heartbreak," Oo said. "To be gunned down in front of a parent? It would break your heart."

Photo by STR/AFP via Getty Images

More than three months after the military seized control, the death toll continues to climb

Kapi said he fears the carnage won't stop any time soon.

"The military has ... killed too many people," he said. "There is no return to normal or to the previous status quo without them paying the price for what they have done. They will continue to fight and more lives will be lost."

All three expats offered their own ideas for possible solutions.

Oo, as a leader in the technology sector, said he wants companies like Google and Facebook to help protesters with internet connectivity on the ground, while Htun called on businesses that operate in the country, like Chevron and Total, to cut ties with the Burmese military and refuse to legitimize the dictatorship.

Kapi is focusing his energy on supporting the National Unity Government, a body composed of ousted members of parliament and anti-coup leaders claiming to be the legitimate government and aiming to restore democracy in the country.

But among the three expats, there was one thing on which they all agreed: Myanmar's crisis will not end unless the international community steps in.

There has been movement from the country's international allies - the Biden administration announced sanctions against Myanmar's military almost immediately; a United Nations commissioner warned the country was on the verge of a "full-blown conflict" earlier this month; and international leaders from Barack Obama to Myanmar's UN ambassador have publicly decried the coup.

AP Photo/Tatan Syuflana

But for the hundreds dead and the millions still fighting, signals and platitudes aren't enough, the expats told Insider.

"I know moral support, political support ... they are there," Kapi said. "But other than that ... we don't get a lot of support for the people of Myanmar who are on the streets, basically fighting bare hands, bare feet against a powerful, well-equipped, ruthless military regime that is supported materially by Russia and the People's Republic of China."

"It's not at all a complex situation," Htun added. "Good versus evil has never been so obvious."

Yet, still, they hold on to hope.

Kapi puts his faith in the younger generation, who has taken charge and refused to succumb to oppression. Oo takes pride in the solidarity seen among all types of people who have come together to fight for a better future. And Htun sees the battle as an expression of love from the protesters for the country they call home.

"My hope is ... we will be able to write a new chapter of our country ... for the people in Myanmar in the near future," Kapi said.